Can public expenditure be egalitarian? This question is all but absent in discussions on Budget 2019 . It is the so-called efficiency question that dominates. The efficiency question seeks legitimate answers in the ratios of debt, expenditure and revenue to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). If these measures are acceptable, investors will tick boxes and potentially invest. Those advancing the efficiency question would argue that this kickstarts a cycle of growth in the economy. In the context of state capture, this approach appears reasonable, even an optimal development outcome. Answering the question however needs not just spreadsheets, but a recognition of the structural barriers facing people that exclude people from the economy. Posing the equity question opens up questions on employment creation and wealth building in a low economic growth environment. Jobs, in an equity-based approach, drives economic growth.

Budget Imaginaries

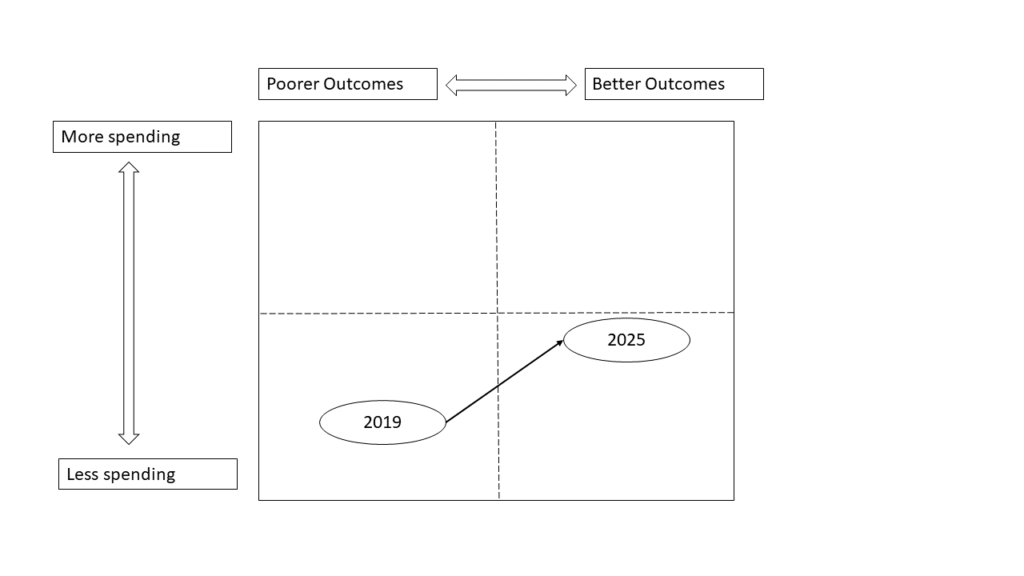

Imagine a simple 2×2 box, which plots:

- Available resources on the vertical axis, labelled as ‘less spending’ and ‘more spending’;

- Impacts of these resources on the horizontal axis labelled as ‘poorer outcomes’ and ‘better outcomes’.

South Africa is in the bottom life quadrant with less spending and poorer outcomes:

- Less spending: deficits have grown, and tax collection underperformed resulting in downward revision to the budget.

- Poorer outcomes: Data on unemployment, poverty and inequality shows that conditions stay the same over a decade or have worsened.

The figure above sketches the envisaged pathway. This pathway:

- Moderately increases government spending;

- Reprioritises and reallocates existing budgets; and

- Seeks to improve outcomes.

Importantly this pathway recognises limits to increasing spending but suggests much better development outcomes within the next five years.

This pathway to improved outcomes will include those excluded from the economy particularly the young unemployed youth and opportunity-based small businesses.

Two proposals would support these groups:

- Expanding the Community Works Programme supplies lower skilled jobs at the minimum wage, potentially to millions.

- Providing small business with system of zero taxation, and a streamlined set of services provided by the state. (For the record, according to the Annual Financial Statements, big business gobbles up most subsidies and grants).

These two programmes aim to include more people in the economy and respond to the structural issues in our economy.

These are not silver bullets, merely an alternative prioritisation. Moreover, substantive reprioritisation of the budget is plausible, and desirable.

Reprioritisation

These proposals are financed by:

- Community Works Programme expansion –.The rapid expansion of the existing programme, would be financed through reprioritisation of spending.

- Zero taxation for small business – This is primarily an administrative act of registering as a ‘zero taxation small business’ . The trade-off is potential losses in taxes, but potentially more employers.

Three contributions emerge from these proposals:

- Employment in the immediate: The current focus on ‘infrastructure’ and ‘industrialisation’ needs questioning on many levels. One criticism is that these are long term investments whose efficacy is mediated through economic multipliers that may not emerge. The proposals in this article are not panaceas but intervene in the immediate and need fewer economic multipliers to occur for inclusion to occur. Designing these programmes however needs careful consideration, especially if women are too benefit from these interventions.

- Scaling quickly but avoiding risk: The proposal for a zero-taxation system for small business is implementable, but the outcome is unclear. There is uncertainty whether tax revenue will decrease or whether many new firms will emerge. However, the proposal may spur entrepreneurship and create more potential employers due to its boldness. Similarly, the expansion of a CWP type programme could over time (and provided it is working) combine a range of government spending.

- Small changes for deeper change: The programmes suggested are set in the context of deep inequality and barriers to upward social mobility. The intent here is to learn about transitions, and through that inform efforts around infrastructure and industrialisation. In a sense, it makes both policy processes responsive to immediate needs and informs infrastructure and industrialisation efforts. It also provides people with “something”, and that increases capabilities.

Conclusion

The proposal presented are a thought exercise. The proposals presented are more coherent for four related reasons:

- Increases the possibility for employment in a low economic environment;

- Provides transparent and monitorable transfers to excluded South Africans;

- Ringfences ‘inclusion spending’; protecting it from the clutches of inefficient SOEs and those with established claims on the budget; and

- New community based and individually held assets are created, which they make a small contribution to equalising wealth and gender-based inequities.

In sum, space exists for experiments that support economic inclusion, especially supporting job creation. However, this is one set of proposals. Other proposals exist, and a developmental state would decide between these proposals. It however does so by managing the fiscus in ways that strengthen inclusion. It is time to reassert the equity question back into the debate.