We are a nation of dot connectors, yet some dot connections are more equal than others.

The Public Procurement Bill (PDF) released by the National Treasury should connect the dots from the State Capture Commission and use this experience to propel a reform agenda. The Public Procurement Bill makes many useful interventions. Taken together these interventions will however not provide a system needed to protect public monies from scurrilous networks. This article argues that a solution lies in ‘open contracting’ which shifts power to citizens and disrupts scurrilous networks.

The Initial Response to State Capture

Fixing procurement has already resulted in pilots. These pilots include:

- Centralisation. The establishment of the office of the chief procurement office and the introduction of transversal contracts are examples of this.

- Open Tenders. Government departments including the Gauteng Province and Department of Public Works now run tender processes in which public can participate.

- Internal audits. Improve compliance within departments has had success in many departments.

These reforms are significant . The people running internal audits or open tenders however raise the central weakness: oversight happens after a decision to (a) run a tender or (b) appoint a service provider are made. The challenge is how to add rigour and transparency before decisions are made.

The major reform in the PublicProcurement Bill bill is the establishment of a regulatory body. A regulatory body to provide oversight and adjudicate disputes is needed. However, it only has substantive powers once decisions are made. An open contracting system happens while decisions are being made and reduces the need for post-decision evaluation. This would allow the regulator to focus on systemic interventions rather than disputes

Open Contracting

‘Open contracting’ is what it says – contracting undertaken transparently and supported by extensive use of technology. In our context, the backdrop of state capture and political will for reform make South Africa a viable candidate to join a range of experiments across the globe. This article deliberately avoids technical jargon. The ideas discussed combine ideas of open contracting with idea of a distributed ledger, which is the cornerstone of blockchain technology.

The best way to understand is to outline how it would function in practice.

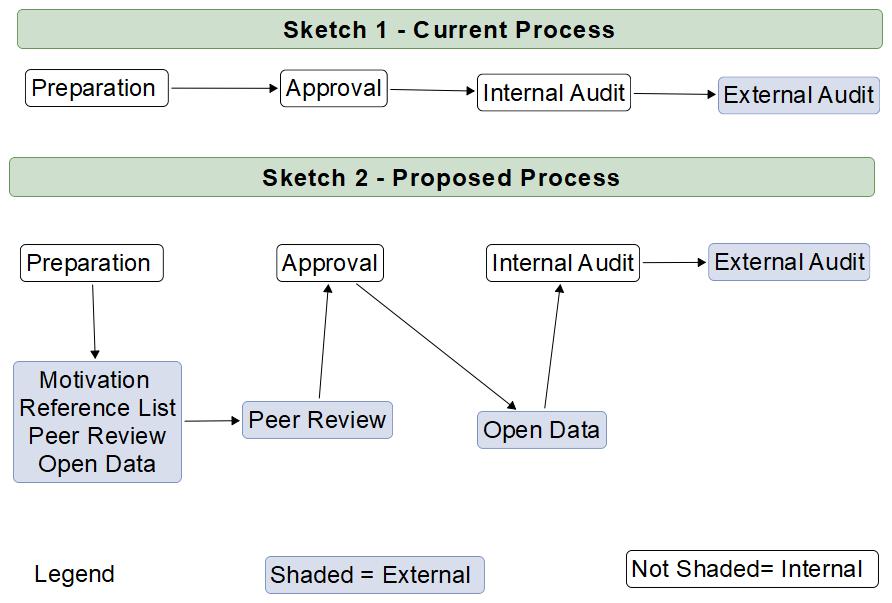

The sketches below an overview of the what the existing system (Sketch 1) and an open contracting model (Sketch 2).

Current Process – Sketch 1

The current process occurs government departments, the proverbial silo. The decisions to (a) undertake a tender or (b) appoint a service provider are made within the department with reference to relevant legislation and records. Our experience shows that the system is not only open to rigging but also excessive spending.

Sketch 2 – Open Contracting

The open contracting model (Sketch 2) increases transparency by:

- Gathering information as to why and how much government will sign a contract. This includes motivations, referencing pricing data and peer review.

- Requiring a peer review process before decisions are finalised. A skilled public service manager – randomly selected – would review decisions and communicate an opinion, including to observers. These can be done in hours not days or weeks, with proper systems.

- The data is public and structured thus supporting the use of algorithms to detect corruption and improve spending. This empowers civil society organisations who can access information and participate throughout the process.

In a decade of implementing this idea, the results will include:

- The cost of procurement and outsourcing vs inhouse delivery would be transparent.

- A credible list of prices would improve budget choices.

- Machine learning would support early warning signalling system.

- Activist organisations would have the information available.

- The formation of scurrilous networks would be significantly harder.

- Small business would benefit as the system would be support enforcement of set-asides.

The starting point is however low tech. A team would focus on understanding procurement for a year. The reason for doing this is to build systems based on experiences. To illustrate, buying gloves for nurses is different from buying generators for all schools in a district is different from enlisting the services of a consultants. The intent is to learn the system for a range of services and use these learnings to design new systems within the capacity and other constraints. This manual starting point would inform the development of a tech-based platform.

Such a reform process should form part of the Public Procurement Act.

Imagine: Ten year down the line a PHD candidate runs an experimental version of her algorithm and finds anomalies in proposed spending on early childhood development. The data is shared with organisations working on ECD and parliamentarians. The dots are connected before the decision are made.

In this world, all dot connectors are equal.